Over the last 15 years, mountain bike suspension systems have become incredibly sophisticated with more adjustability than one could ever hope for. They’ve become lighter, smarter, easier to adjust, and more effective. A lot of this technology has trickled down from the motorcycle world carrying with it the added challenge of fitting it within a much smaller and lighter fork or shock package to suit the changing demands of mountain biking. Suspension, like any high end machine, requires some specific setup and maintenance to work optimally, especially with many of the industry’s leading suspension frame designs that can rely heavily on the correct setup of suspension systems to reach their full potential.

Are you comfortable with the performance of your fork or shock? Have you ever found difficulty in finding that ‘sweet spot’ for settings that just feel perfect? Maybe you’ve never adjusted them before or never knew you could. Either way, before you go and lash out on a new latest and greatest, take the time to understand the adjustments, check the settings and learn about modifications to make it work better for you. Let’s start by diving into all those shiny coloured knobs and dials, what they’re for and how they work:

WHAT ARE ALL THESE ADJUSTMENTS?

There are basically three main common types of external adjustment on most suspension forks and shocks.

SPRING/PRELOAD

This is the adjustment of either a spring pre-loader knob or spring rate (coil forks) and preload collar (coil shocks), or, most commonly it is the adjustment of the air spring pressure. This is adjusted using a shock pump, and allows us to set pressure based on weight via either the manufacturers recommendation, or via a basic setup with the rider (more on this later). The benefit of an air fork or shock is that they are generally pretty user friendly to modify for rider preferences. not only can you easily adjust your air spring pressure by using a shock pump, you can also change its rate of compression by modifying the volume of the internal air chamber with variations of volume spacers. for forks these are sometimes referred to as ‘tuning pucks’ or ‘bottomless tokens’, and for most shocks there are air volume spacers and varying volume air cans.

Here is a Fox Float air can, vs the new Fox EVOL air can from the Float DPS shock. (Note - The EVOL air can is a retro fit option for most older Fox Float shocks)

WHAT DO THEY DO:

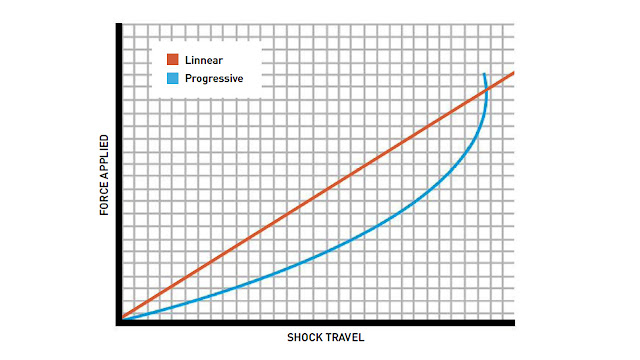

- Installing air spring volume spacers can effectively reduce the amount of air volume inside, which in turn will make the fork or shock feel more progressive and ‘ramp-up’ sooner in its travel, reducing its likelihood of bottoming out. This is common in shorter travel forks and shocks, especially those being used for cross-country riding and racing with 80-100mm travel, although they also can be used in longer travel forks or shocks to achieve a more progressive feel.

- Removing air spring spacers can increase the volume of air inside, creating a more linear rate of compression that can feel plusher, easier to bottom out and even more sensitive for small bump compliance, although it can adversely affect the performance of the fork or shock if the spring rate or pressure setting is not spot on. The removal of these types of air spring spacers, and effectively increasing the volume of the the air chamber is reasonably common for lighter riders (less than 65kg) struggling to properly ‘use’ all that fork or shock travel they have on board. Another way of achieving a more ‘linear’ and or ‘bottomless’ feel in air sprung rear shocks can be by using a higher volume air can, which is a popular aftermarket upgrade for even older shocks with several options now available for most brands. Another benefit of a larger volume air can is often an increase in the small bump sensitivity of the shock.

COMPRESSION

This is the adjustment of how firmly or softly a fork or shock will travel throughout its stroke. Compression damping adjusters control the fork or shock’s speed at which it compresses as it hits a trail feature or obstacle and can have a massive impact on how a fork or shock rides, regardless of the accuracy of the air spring pressures. Compression adjusters control the flow of oil through the internal damper’s shim and piston assemblies. In basic terms, the thinner the shim stack, and the wider the mouth or ‘holes’ in the compression piston, the easier it will be for oil to flow and the fork to compress. This is one of the most commonly modified parts of a suspension fork or shock and is done internally by reconfiguring the compression shim stack within the fork or shock’s oil damper system. Sometimes, the rate of compression is also adjusted by using differently weighted oils inside the fork or shock. For example: A heavier oil will flow through the piston harder and slower than a lighter weight oil, therefore a heavier rider wishing to increase the rate of compression without modifying the internals may consider a heavier weight oil, and vice versa.

In many cases, there are adjustments for ‘high speed’ compression, and adjustments for ‘low-speed’ compression. but what’s the difference?

HIGH-SPEED COMPRESISON (HSC)

HSC adjustment controls the fork or shock’s movement under a fast or sudden impact such as hitting a rock or root mid trail, or the heavy landing off a jump. It is an adjustment more commonly found on longer travel forks and shocks to control the stability of the bike during the sudden impacts and consecutive hard hits.

LOW-SPEED COMPRESSION (LSC)

LSC adjustment controls the fork or shock’s movement under general pedalling forces, small bumps including trail surface undulations and even braking. LSC adjustment is more commonly found as an external adjuster than it’s highspeed counterpart, and it is also commonly found on forks or shocks with a multiple position compression adjuster/ lever. This generally allows the rider to choose between soft, medium and firm LSC settings depending on the terrain or style of riding.

For example, The Fox CTD (Climb Trail Descend) ‘Trail Adjust’ range of forks and shocks allows you to fine tune the ‘Trail’ setting, which is allowing you to externally customize how soft or firm you would like the LSC stroke to feel in that middle ‘Trail’ position. The popular RockShox Pike RCT3 fork also has a comparable degree of external adjustability to it’s nearest rival, however the specific LSC adjustment only has an effect when the compression dial is set fully open.

SO WHY WOULD I ADJUST MY LOW-SPEED COMPRESSION?

Whilst it would be awesome if our Monday to Fridays consisted of downward trails for days, in reality they don’t, and we need to climb, and pedal (and work dammit)! So with consideration firstly to pedalling efficiency, the more LSC that you turn on, the more likely the fork or shock will feel more stable under pedalling forces, and the pedal ‘bob’ will be reduced. With less LSC turned on, you will more than likely experience more pedalling induced bob, and in forks, you may experience an increase in front end ‘brakedive’ during heavy braking. With many of our managed trail networks featuring flowing berms, lots of pedalling and sometimes a limited number of heavy HSC hits, it can often be more efficient for the average rider to ride those trails in the middle setting that is set to your desired feel. Secondly, as you may adjust your air pressures for particular events, riding locations, or following a modification of the air volume inside, you may then also find the need to make small adjustments to the LSC adjuster to fine tune your ride’s performance accordingly.

HOW DOES THE COMPRESSION DAMPER’S LOCKOUT FUNCTION WORK?

This is the most common form of compression adjustment as it quite simply allows us to fully control the fork or shock’s range of movement, from fully ‘open’, to fully ‘closed’ and often many settings in between. When you turn that lever or dial to the ‘lockout’ position, you are basically mechanically closing the compression damper and piston assembly inside, stopping oil from being able to flow through it, and thus stopping the fork or shock from being able to compress. While there are many varying methods in which the suspension gurus have designed the lockout function, they will almost always have a form of ‘blow-through’ that allows oil to bypass that closed circuit in the event of a high speed impact or for those times when you forget to unlock before that gnarly drop.

REBOUND

This is the adjustment of how fast or slow a fork or shock is able to extend back to it’s neutral position following an impact. If your rebound adjustment is fully open or turned counter-clockwise to the limit, it will be in its fastest setting, which for most forks or shocks will give the rider a ‘pogo-stick’ kind of feel, often resulting in the trail feeling rougher than it actually is! This can lead to several adverse affects such as ‘bucking’ your front or back wheel sky high when tackling higher speed obstacles including the up-ramp off jumps and the aftermath of heavy landings. On the flip side, if you wind your rebound adjusters all the way inwards (clockwise), you will then be in the slowest setting which for most forks or shocks will translate to a severely harsh trail feel to the rider. This is because you are not allowing the fork or shock enough time following an impact to react and return to its neutral position before it takes the next impact, and in effect it begins to ‘pack-down’ into its travel. A 140mm travel fork can quickly feel like a 80mm travel fork with rebound settings too slow.

COMMON REBOUND QUESTIONS

ok, so too fast is bad, and too slow is bad, so where do i set my rebound?

This is a hard one to answer directly as every rider, bike and terrain combination will have a different setting, however I will confidently say that the majority of us will be satisfied with our rebound being set at a couple of turns on the faster side of the mid point of adjustment. ie, if your rebound dial in the fork or shock has 5 full turns (or clicks) of adjustment from fully out to fully wound in, you will more than likely be happy with 1-2 full turns (or clicks) inwards of that rebound knob from fully unwound. That’s a good starting point, then you can make small changes as you see fit with consideration to the differences explained above between ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ rebound, and that with varying weighted riders the rebound settings will differ.

can you modify a fork or shock’s rebound adjustment range internally?

Yes, the rebound settings are also ‘tunable’ in most forks and shocks, and will normally be done by reconfiguring the rebound shim stack within the fork or shocks rebound damper circuit. For example: If you are happy with your air spring pressures used, but are finding the rebound adjustment at its fully un-wound or ‘fastest’ position is still too slow, you may feel the fork or shock rides harsh and lacks compliance. This would be a good reason to ‘tune’ the rebound circuit to achieve a controlled but faster flow of oil back through the rebound piston and shim stack resulting in an overall faster rebound rate. Following an internal ‘tune’ or modification, you would then be able to make the fine adjustments to your new preferred settings using the external rebound knob.

my rebound adjuster doesn’t seem to do anything?

If the fork or shock’s rebound adjustment is not apparent at all throughout its full range of the adjuster, there’s a good chance that the fork or shock’s damper has lost oil, and is in need of some loving and a good service. Loss of any rebound control is often a dead giveaway for a ‘blown’ or severely aerated and cavitated damper, as when oil has leaked or blown out from the damper assembly, it allows little to no path of resistance for the rebound piston/damper to extend, and thus it usually extends violently with often a nasty ‘top-out’ feeling.

ROUTINE SERVICING, AND WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

Just like your car, routine servicing is crucial to get the most out of your fork or shock. Most manufacturers will have routine service recommendations generally between 40 and 100hrs use which for most of us will be annually at the very minimum. Although it can cost more in the long run, regular servicing allows for many years of happy trails without spending up big on replacements and improves the performance of the fork or shock. And that’s a win!

‘My forks are working fine, they are just due for a service’.

It is quite common for a fork to come in for service that feels just ‘fi ne’, however the condition on the inside often tells a different story. It is not uncommon to fi nd blackened contaminated damper oil, dry lower legs, perished seals, worn stanchions and so on. So whilst they may be working ok, it is quite possible they are working well below the performance potential.

As you ride your bike, deep within the guts of your fork or shock is a complex array of seals, shafts, shims, pistons and bushings that allow for the complex damper systems within to work. Over time, in normal mountain bike use there will be contaminants such as dust that will make their way through the dust seals as they wear. Although it’s unlikely that dust will cause any major catastrophes within the fork or shock’s internals, it will almost certainly affect its performance by drying out the inside, and if dust can get in, it will allow oil to get out. Additionally, over time the seals or bladders containing the oil within the damper will perish, wear and fl atten and in turn lose their ability to properly seal the oil within the damper body. Eventually, the oil within the damper becomes aerated and that can quickly translate to loss of functionality at the external adjusters.

In rear shocks, this is sometimes referred to as cavitation i.e. when nitrogen or air from a shocks internal fl oating piston (IFP) chamber escapes and mixes with the oil, leaving you with that squelchy feeling and signifi cant performance loss.(See images to left) The pic shows a cavitated shock damper that has also lost a signifi cant amount of oil through the shocks main (but worn) seal head assembly and adjusters. As a result, there was little function in the lockout lever unit, and the shock rode like a ‘pogostick’. The second picture shows what the same shock damper body looks like during the reconstruction and pre bleed process, with a bubble free and clean oil ‹meniscus›.

In forks, it is all too common to see severe damage to the stanchions, often referred to as the CSU - Crown Steerer Unit (See image to the left). This is usually a result of poor lubrication in the lowers, bushing wear and or seal/ foam ring contamination, most of which are avoided by regularly cleaning, inspecting and maintaining reasonable service intervals. Although these are all replaceable parts, the costs can sometimes get out of control when a fork may end up requiring a service, seals, bushings and new (CSU) stanchions just to get it trail worthy again.

SETTING UP AIR PRESSURES:

Correct suspension setup is vital to maintaining general balance, pedalling effi ciency and to effectively achieve the full amount of travel in a fork or shock without the harsh bottom outs. So let’s go through just the basics with a few added tips to make live easier.

Sag - ‘The amount your fork or shock will move into its travel with just your ‘riding’ weight.’

To measure sag, you will need your bike, your riding gear and a shock pump. Make sure you set any adjusters on the bike to fully open. Unlock that lockout and or wind out any LSC dials on the fork or shock. Move your sag indicator o-ring as close to the fork or shocks dust seal. For the next part, set the bike up approximately 50cm from a wall running parallel so you can lean against the wall while seated on the bike. Whilst in your riding gear including the backpack (if you use one, see tips below for more on this) carefully climb onto the bike and rise up into a neutral riding position, which is not seated, nor leaning over the front of the bike, It should be out of the saddle, arms bent and with your weight fairly central over the bike.

Next up, have a friend help you here if you can, and examine where the little sag indicator o-ring moves to on the fork’s stanchion or shock’s damper body with your body weight centralised. Then, carefully climb off the bike, and measure the distance the o’ring has moved as a percentage of the total stanchion or damper body length/stroke or travel. This part can take some patience and many attempts to really dial in the correct amount of sag, which for most of us will sit between 15 and 35% depending on the bike, rider, terrain and event.

Here’s a general idea of sag percentages:

15-25% Sag for the more XC type rider and bike 20-35% Sag for the more enduro/DH rider and bike

Once you have ascertained your correct pressure settings based on sag, make sure you take a shock pump with you on that next ride or two just to make small adjustments if required. Keep in mind that this is just a ‘guide’ only, and is a really good starting point.

QUICK TIPS FOR THE ULTIMATE SAG SETUP:

1) Sag should be measured when you are in your common riding gear including your shoes, helmet, backpack and an average amount of water you would normally carry. If you carry a 2litre hydration pack, do your suspension setup with it half full, to achieve the happy medium with what becomes your ‘average riding weight’.

2) Full suspension bikes can be setup with slightly MORE sag in the rear shock than the front, sometimes as much as 10% extra (up to 35% total), but generally speaking - 5% is fi ne for the average rider.

3) Make sure your shock pump registers the current fork or shock’s pressure on the dial before you start pumping. If it doesn’t register the pressure and you have tightened it onto the fork or shock’s valve as much as possible, then it is possible that either there is an issue with the valve, or more commonly, the pump.

4) Many shock pumps will release a small amount of pressure during the removal from the valve process. This is normal, however it is important to work out exactly how much your pump is losing in the process. Once you have set the shock to 150psi as an example, remove the pump completely then reinstall it again until the pump’s gauge registers the current pressure. Then make note of the difference and keep this in mind next time you’re checking your pressures.

5) If you’re losing more pressure in the pump removal process than you think is acceptable, buy a $5 valve core tightening tool from your local servo, and check that the core is tightened fi rmly and not protruding from the top of the valve stem. Typically, the valve core will sit 0.5-1mm below the top edge of the valve stem.

THE TAKE AWAY

The suspension systems we have at our disposal can make the riding experience far more enjoyable with our wheels glued to the ground and traction for ‘days’ with care and attention to good setup and maintenance. And whilst not all forks and shocks are littered with external adjusters to make or break your ride characteristics, there is almost always a way its performance can be improved with relatively minor modifi cations to suit a rider’s needs. So I hope you have found some of that interesting, and are able to translate some of it to your own fork or shock to reach its full potential. Happy trails!